Shetland News and Shetland Times

Helen Kerr reviews a Prisoner of War writen by Lesley Leslie, directed by Jennie Atkinson, performed by Islesburgh Drama Group and broadcast on BBC Radio Shetland last week

THERE’S magic in storytelling. Trust me, I know. I have read, to seas of young faces, books from bygone days that they may never have read themselves; I’ve witnessed the gasps when you stop for another day, the groans that the story is over until the bell rings again – such is life as an English teacher! And it doesn’t matter how old you are, or what reading ability you have, or what genres you have a preference for…a well-told tale is magic.

The creative and cultural arts have, as have so many sectors across society, taken a hit during Covid. Nestled in the very heart of the performing arts is community. The arts bring people together like many other walks of life can only dream of. They are where we find inspiration and awe, escapism and fantasy, reflections of real life in all its mucky glory…and they are where we find people.

Performers, artists, musicians, actors, dancers…technicians, engineers, managers…the list goes on and that’s before we have even started with the audiences. There is far more to the arts than ‘putting on a show’ – in fact, the correspondence I have often had regarding Islesburgh Drama Group refers to the vast array of people involved in their theatre productions as ‘wir family’. So, when Covid threatens to break up your theatre family, where do you go?

Well, you do what you do best…you tell the story. You just need a new way to do it.

Enter the Islesburgh Drama Group’s first foray into radio drama.

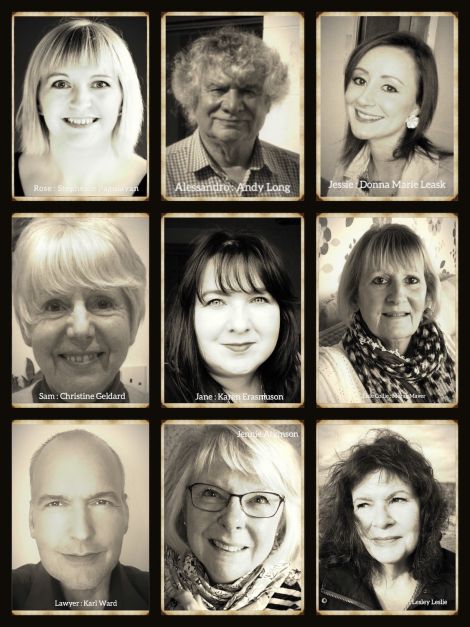

Prisoner of War by local writer Lesley Leslie, tells the story of an unlikely love between Italian prisoner of war Allessandro and Shetlander Rose. Just a half hour long, the play whisks us through their early fractious interactions, to the surprising conclusion where their love had quietly and secretly blossomed. Told alternately as flashbacks between the two protagonists and conversations Rose’s niece Jane had after her aunt’s death, Prisoner of War is bursting with promise as a radio play.

Of course, listening to a story unfold is not the same as watching it. While theatre productions may always possess something of a stylised quality due to the very nature of where the audience is situated, we are afforded all kinds of context clues that tell us where the action is taking place, what it is like there, who is there and what they look like, how mannerisms and facial expressions contribute to the successful building of character. When all those are stripped away – what are you left with? How do you communicate character, emotion, feeling, context when the audience can’t see you?

Of course, radio drama is nothing new. We’ve all heard of – or even heard – the world’s longest running radio play The Archers. You can’t run something successfully for 70 years if it’s not possible. But my, the skill set will stretch you. There is no wink or nod, no eye roll, no crossed arms or friendly wave that will communicate meaning to an audience that can only listen.

So, in gathering their skills and stretching them further with Prisoner of War Islesburgh Drama Group presented us with this tale.

It begins with death. Not a promising or cheery start when you are holed up in your own home on a miserable February evening, for what seems like the millionth night in a row. Jane, our present day narrator, starts to tell of her new discoveries in going through her recently deceased aunt’s belongings. She has found a series of letters and journal entries which, upon picking through them, start to reveal some things about her aunt she never knew.

Jane and her friend Sam speak on the phone, the context of which is given to us through the familiar ring and distanced voice over a landline. These conversations were supposed to provide a narrative structure, of course, although sometimes this felt at the expense of the realism of the calls between the women. There were moments where the dialogue felt forced as though it was there for detail rather than the building of character, but since the play was short and the need for resolution therefore swift, this was entirely forgivable as it did give the piece the momentum and pace it needed to get to the point of the story.

Since the play crosses the spans of time and eras, there is necessity to make these distinctions apparent for a listening audience. No prop or scene changes, or exits and entrances – rather the rise and fall of the music of wartime Britain to signal to the listeners that we were crossing time and space to hear from voices past. Perfectly done, setting the mood as often only music can and whisking us back to when and where Rose and Allessandro started their love affair.

Stephenie Pagulayan’s earnest portrayal of the irritated Rose sets the tone well; vocally – and let’s face it, that’s what we are relying on here – we get it and we get her. Her distaste for Allessandro’s presence is apparent in word and expression and Pagulayan leaves us in no doubt as to how we are to interpret Rose’s earliest experiences with the prisoner of war.

Allessandro is of course in an entirely different situation given his status as a prisoner of war; his voice sounded older and wiser than we might have expected, and sometimes the Italian lilt didn’t feel compelling enough. But no sooner had we settled into their story when we were whisked right out of it and back to Jane and her present day narrative.

Structurally, the play works. To have reports of the voices, and the voices themselves, adds a depth and richness to the storytelling and enabled the climax to build. The introduction of Donna-Marie Leask as the antagonist Jessie gave the story just enough room to twist and bend into a more surprising outcome. As the miserable post-mistress who intercepted letters between the Rose and Allessandro as their love grew, Leask once more shows her versatility as an actor.

And there were other small details in amongst the play – clinking glass and pouring drinks – that as it moved on drew its listening audience in. The only surprising sound detail, for me, were the sudden bursts of Savage Garden’s 1997 hit Truly Madly Deeply which, for the life of me, I couldn’t decide why it had been chosen…was it setting the timeline for story? Was it just a classic love song of its time? I couldn’t decide but thought the play could have lived without it.

The story concluded quickly. Far too quickly. I hadn’t realised until we were 25 minutes in how invested in Rose and Allessandro I had become. It should have – or could have – been the slow unwrapping of a timeless love story. And I found myself wanting it to stop – I wanted the bell to ring and to come back another day and catch the next instalment of what could have easily been a stunning serial drama. I wanted to know Jessie’s motive better and see inside her heart. I wanted the blossoming of love to unfold gently and slowly, to know how it grew and changed in more than passing conversation over a dram. Alas, not to be.

But there we have it. The magic of storytelling. Because even though Rose and Allessandro’s story is not for another day, you can bet your life I’ll be back for the magic when Islesburgh Drama Group come telling again.